Criteria for a Scientific Model: The measuring device as a physical concept

By Louis Marmet - 2019 December 13

Although it is difficult to reach agreement on a precise definition of the scientific method (how science is done), the distinction between physics and mathematics (what is science) should always be clear in the scientist’s mind. Yet, theoretical physicists have developed a habit of putting forward entirely baseless speculations.

To keep physics theories connected with the real world, scientists agree with the criterion ‘Without experimental tests, a theory is not scientific.’ But even if a theory can be tested (falsified or verified) it could remain disconnected from the real world — many mathematical theories are. Therefore, a scientific theory must also be formulated in terms of concepts that are physically possible.

Physical Concepts

The only way to describe the real world is to pay attention to observations. Observations are necessarily obtained from measuring devices which range in complexity from the simple ruler to large particle accelerators and the human eye. In its most basic form, the measuring device has an indicator showing the magnitude of what is being measured.

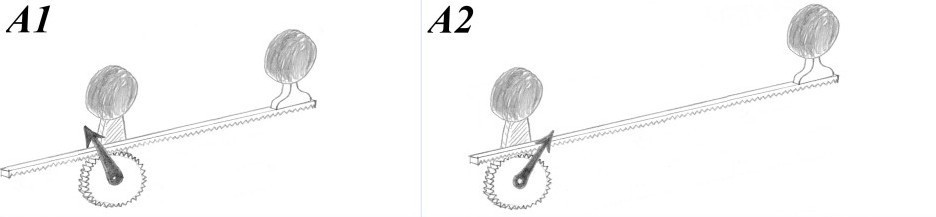

Measurements obtained from a single device are not absolute because the device could be built in any arbitrary way. No single observation has a reality of its own, measurements can only acquire their meaning through comparison. For example, a device A measures the ‘distance’ between two balls. A copy of the device may show a different position of the indicator, such as in cases A1 and A2. However, if the balls of device A1 are aligned with those of device A2 the indicators will have the same positions, confirming that distance measurements are reliable.

Device A: A needle indicator is attached to a pinion in the familiar rack-and-pinion configuration. The pinion rotates about an axis attached to a vertical plate which supports a ball (left). Another ball is attached to the far end of the rack (right).

One therefore determines if measurements ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ based on a comparison between two indicators. Such a comparison represents the basic process involved in all measurements made by physicists, from the mass of an electron to the size of a galaxy. As such, this device defines what physicists mean by ‘distance’.

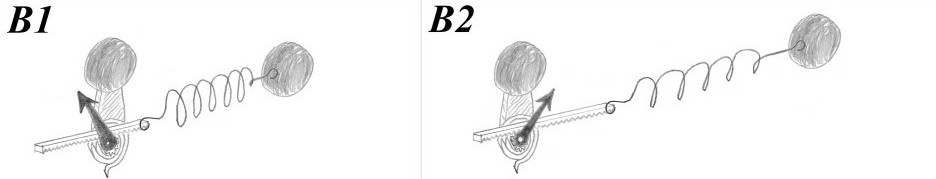

It is rather trivial that a device and its copy in the same configuration would always produce measurements that agree with each other. The comparison process becomes powerful when fundamentally different devices are available for comparisons. For example, we can have a slightly more complex device which measures the ‘elastic force’ of a coil spring attached to two balls. Device B is constructed in such a way that for balls aligned with those of cases A1 and A2, the same measurements are obtained. (This restriction makes comparisons between A and B easier.)

Device B: A needle indicator is attached to a small pinion which is held by a spiral spring. The other end of the spring is attached to a vertical plate supporting a ball. A short rack drives the pinion. The right-hand end of the rack is attached to a large coil spring which is in turn attached to another ball.

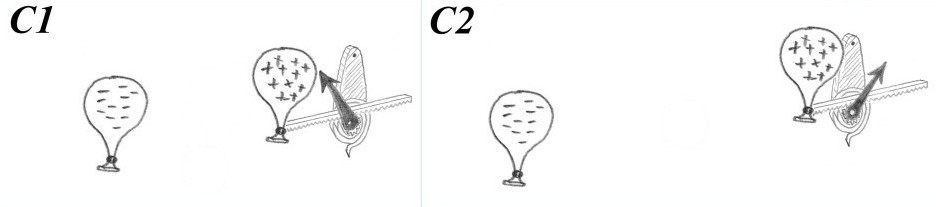

For the following discussion, we also introduce device C which measures the ‘electrostatic force’ between opposite charges. Again, the device is constructed in such a way that for charged balloons that are aligned with the balls of cases A1 and A2, the same measurements are obtained.

Device C: The spring-loaded rack-and-pinion indicator is attached to a positively charged balloon on the right. The balloon on the left has a negative charge that will attract positive charges. Charged balloons are produced with the usual method involving cats.

Physicists agree that these devices define what is meant by ‘distance’, ‘elastic force’ and ‘electrostatic force’. As a consequence, a measuring device not only produces observations but it also concretizes the language used by the scientist. This leads us to the ‘measuring-device criterion’: Every physical concept is defined by a measuring device.

Testing a Model

With these notions at hand and the concepts of distance, elastic force and electrostatic force, the curiosity driven scientist will ask the question: ‘If the objects being measured by devices A, B and C are kept aligned, will the measurements agree for object separations which are not those of cases 1 or 2?’

Before answering the question with an experiment, a hypothesis is made relating devices A and B:

‘When the objects of devices A and B are aligned, the measurements from A and B are the same for any distance.’

Here, device A is proposed as a model for the elastic force and experimentation with other distances will show that indeed, this hypothesis holds. Repeated experimentation will be necessary to increase our confidence in the model. With repeated experimentation, the hypothesis of this example has become the theory of elasticity stated in terms of two physical concepts: ‘distance’ and ‘elastic force’. These two concepts have a common characteristic which is referred to as Hooke’s law.

Experimentation serves both purposes of testing the theory (for possible falsifiability) and testing the devices (for possible defects). This is how science discovers remarkable properties of nature: two apparently disconnected and unrelated phenomena have a common measurable characteristic.

Based on devices A and C, a second hypothesis can be made:

‘When the objects of devices A and C are aligned, the measurements from A and C are the same for any distance.’

In this case, device A is proposed as a model for the electrostatic force. However, the hypothesis will fail when the objects are moved to other positions. The electrostatic force between two objects does not behave in the same way as the distance does.

The measuring-device criterion is essential for any attempt at demarcation between concepts and theories that are scientific and those that are disconnected from the real world. Experimental tests verify (if existential, e.g. “some swans are black”) or falsify (if universal, e.g. “all swans are white”) a correspondence between different types of observations (using the concepts of ‘swan’, ‘black’ and ‘white’).

Mathematics: Proceed with Caution

Hypotheses are made, models are proposed and theories are tested before any reference to a mathematical structure is even needed. This is because these are all part of a self-contained process based on comparisons between measuring devices. Physics operates based on observations, concepts, hypotheses and experimental tests - four elements recognizable in the scientific method.

Mathematics is a powerful tool that has been used by physicists for centuries. But a mathematical description can go beyond what is observed in the real world. Mathematics has no problem describing imaginary numbers, fractional dimensions, the infinity of integer numbers, and even infinities that are larger than the infinity of integer numbers, but these concepts don’t even hold “promise of making contact with empirical evidence”.

Undoubtedly, mathematics is a very powerful tool which can efficiently describe physical concepts and observations. Expressed in a mathematical language, the above discussion is written:

“Distance is \(d\); \(k\) and \(l\) are some constants. The elastic force \(F_\text{H} = kd\) is Hooke’s law, but the electrostatic force model \(F_\text{E} \propto l-d\) fails to predict observations.”

However, mathematics is a formal language which can also generate concepts that are not defined in terms of a measuring device. As a result, mathematical models lose their connection to reality if they stop satisfying the measuring-device criterion. The danger with mathematical models is that they can successfully provide accurate curve fitting even if the models have no basis in reality. The appeal of that success has encouraged a large number of theorists to publish, but “the criteria for what counts as “theoretically possible” in the foundations of physics today are so weak that writing papers about observing these theoretical possibilities is just wasting everybody’s time. It’s science fiction with equations.”

When mathematical notions are introduced into a theory, the connection with the real world is lost if they not defined in terms of a measuring device. Examples are:

-

If a proposed cosmology is purely mathematical (e.g. “the universe has ten dimensions”) and is not formulated in terms of measuring devices (e.g. “what device measures the number of dimensions”), it has no physical meaning and cannot be studied by science.

-

The concept of infinity is purely mathematical. No device can generate an observation of ‘infinity’; there is no physical concept associated with it. In the real world, the amount of money in your bank account will never become infinite.

-

A device does not reveal the “truth” about distance, force or any other physical observable. The only truth is our metaphysical confidence that our logic can be used to argue about truth and the foundations of physics. Believing in the scientific method is a metaphysical choice made by the scientist, a choice that is not supported by science! Since we can’t build a device with an indicator that will show ‘true’ or ‘false’, “Truth” is not a physical concept. While no observation has a reality of its own, physical concepts and theories express relationships that describe the real world.

A Scientific Model

The power of mathematics cannot generate any new physical concept, even if the equations are “simple” or “beautiful”. Every concept used in physics, such as distance, time, velocity, mass, and force, must be defined by a measuring device. Any other concept is disconnected from the real world, does not produce observations and cannot be subjected to the scientific method.

It is important to keep in mind the distinction between physics and mathematics as it impacts on which statements have physical meaning.

-

Claims such as “equations lead to correct predictions” and “observations falsify equations” only reflect a poor understanding of science. As described above, tests are made independently of a mathematical structure. A mathematical equation cannot be tested against observations. It is the physical concept that is being tested experimentally.

-

Theories have limits of applicability, not because of some arbitrary weakness but because beyond those limits physical theories tell us that the experiment breaks the device. (E.g. the spring of ‘Hooke’s law’ breaks if stretched beyond the limit of elasticity.) Without a working device there is no observation and therefore no science.

For example, general relativity tells us that near a black hole the gravitational field gradient will break any physical device. Inside that ‘break-down radius’ no physical concept can exist. Schwarzschild calculated a relativistic solution and Hawking said “there is no event horizon”, but this is all irrelevant to physics since the entire “black hole” is inside the ‘break-down radius’ where no scientific concept is valid.

All that considered, the Big Bang model is far from a satisfying scientific construction. “Big Bang singularity”, “inflation”, “a state so hot that the laws of physics are different”, “dark matter” and “dark energy” are all mathematical models: none of those is supported by a comparison of results from measuring devices. The Big Bang model is pure mathematical speculation which has no chance of being even remotely scientific since it is not based on physical concepts. This explains why everything about the model keeps being revised: the age and shape of the universe, the distribution of matter, the accelerated expansion, the predictions of the CMBR temperature, the quantity of Lithium, etc. Being disconnected from reality it can take any arbitrary shape or form.

“Theorists have been cunning and inventive. They have plenty of metaphysical ideas but there are no empirical signposts telling them which path they should take.” Yet, additional guidance can be obtained form these criteria:

-

A model must be verifiable (existential claim) or falsifiable (universal claim), and

-

every physical concept must be defined by a measuring device.

These criteria are essential for the productive development of a cosmological model.

© 2020–2023 Louis Marmet